The NFHS Runner’s Lane Rule: Umpire’s Guide

This Special Report was written by Rick Roder, author of The Rules of Professional Baseball:

A Comprehensive Reorganization and Clarification. Email Rick, rick@nullrulesofbaseball.com

Baseball’s running lane rule got its day in the sun in Game 6 of the 2019 World Series.

Plate umpire Sam Holbrook ruled that Washington Senators’ batter-runner Trea Turner violated the rule by running outside the lane, thus interfering with the ability of the first baseman to receive the throw from the pitcher, who was in the vicinity of home plate.

As with any play in sports wherein the only people aware of a problem are the official watching for it and the players immediately affected, the crowd and announcers were stunned that someone had been called out. The ruling was upheld after video review.

Reflecting on this play, one NFHS leader stated that the running lane interference rule is the most-missed rule in high school baseball because coaches “go nuts” when it is called. Umpires are reluctant to go out on a limb and call the violation, knowing they can probably skate with a no-call. This negligence results in batter-runners doing whatever they want, not having been coached to stay within the running lane. Worst of all it results in an unfair situation for defensive players looking for a fair chance to put the batter-runner out.

Let’s look at the rule, its enforcement and its nuances.

NFHS 8-4-1-g

The batter-runner is out when

(g) he runs outside the three-foot running lane (last half of the distance from home plate to first base) while the ball is being fielded or thrown to first base.

- This infraction is ignored if it is to avoid a fielder who is attempting to field the batted ball or if the act does not interfere with a fielder or a throw.

- The batter runner is considered outside the running lane lines if either foot is outside either line.

Keeping It Between the White Lines

The best way to break down this rule for purposes of learning and enforcing it well is to follow the task list of a well-trained plate umpire.

After ruling on a fair or foul ball, the plate umpire is to move to the first base foul line (staying outside fair territory if there is a chance a runner will score on the play). Here the plate umpire has only one immediate responsibility: make sure the batter-runner is complying with the running lane rule.

It is important to note that the rule does not come into play until the batter-runner reaches the half-way mark of the journey to first base. There should be a line painted or chalked on the field indicating the 45-foot point.

There should also be a line in foul territory, parallel to the first baseline and forming a long three-foot wide lane. For trivia buffs the “three-foot running lane” is actually wider than three feet. This is because the first base line is completely within fair territory and the rule creates a three foot wide area in foul territory. Thus the running lane contains the three feet of foul ground plus the width of the first base line.

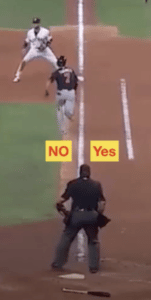

Sam Holbrook in perfect position to make the call

While watching for compliance by the runner, the plate umpire should first straddle the first base line (or first base line extended if there is a chance a runner will score). If you check the official MLB video (below) of Holbrook’s World Series play you will see him in perfect position to see the play, straddling the line. Then watch to see where the batter-runner’s feet are landing. If his steps are coming down on or within the running lane, he is within the limits of the rule. Also, common sense and 8-4-1-g (1) would reveal that if the batter-runner is far inside or outside the running lane, but is doing so to get completely out of the line of the fielder’s throw to first base (or to avoid a fielder), then he is not in violation of the rule.

If the batter-runner is running within the lane, the plate umpire will see that his compliance with the rule opens up a “throwing lane” for the fielder who is setting up to throw the ball to first base. This is the purpose of the rule.

The Fielder Throwing

Having set up the requirements of the runner, it is now time to talk about the fielder making the throw.

It helps to know that when it comes to the running lane rule, there is an important difference between OBR and NFHS enforcement, and the difference lies with the fielder making the throw.

Under the professional baseball interpretation of this play, the throw must be a decent one and the running lane rule is “off” if the throw is widely errant. In fact, many professional managers and coaches teach the player making the throw (usually a catcher) to “drill” the batter-runner in the back when he is running outside the lane. Most players are decent enough to just try to make a good throw to the player covering the bag. The reason for this situation is that the Official Rules say that the rule is only to be enforced if the batter-runner interferes with the fielder taking the throw; not with the fielder making the throw. Of course in games played under Official Rules, the players are usually well coached and have an advanced skill set.

The NFHS would of course like to make sure that a fielder is never put into a position to intentionally throw at the batter-runner in order to get the rule enforced. Additionally, the players (and possibly their coaches) are often novices. Thus the NFHS does not require that the fielder making the throw make a good throw. In fact, a careful reading of the NFHS running lane rule reveals that it does not specify which fielder is affected by the batter-runner’s violation. Thus, if the fielder tries to lob it over the runner, or dives out one way or another while trying to make the throw, etc., and the throw goes wild, the batter-runner is still to be called out for interference.

The Fielder Receiving the Ball at First Base

The point at which many people finally realized that Sam Holbrook got the running lane interference correct was when they saw the slow-mo of the fielder trying to make the play at first base.

The first baseman was obviously hindered well before the ball arrived and in fact appeared to try to “reach through” the batter-runner to catch the ball, only to have his glove torn away due to the contact.

Add to this that had the batter-runner chosen to comply with the rule, he would have been coming into first base bag at a completely different angle, one that likely would have allowed the first baseman the “lane” to receive the throw unhindered.

One goal every umpire should have when developing as a plate umpire is to make sure that he or she is just as aware of how unfair it is that a runner runs outside of the running lane as the fielder at first trying to make a play on the ball. Umpiring, after all, is ultimately about fairness.

Some Other (Important) Tidbits

- When considering this rule it is important to realize that the first base bag is completely in fair territory; the base is completely outside the running lane. Obviously, a batter-runner needs to step out of the running lane to touch first base. He is thus allowed this leeway in his final thrust for first base without being called out for running lane interference provided he was in the lane prior to his step or reach for the base. This aspect of the rule is clearly covered in the Official Rules and is common sense in all other rule codes.

- The line marking the 45-foot (half-way) point of the distance to first base is important. The rule does not come into play until the batter-runner reaches the half-way mark. He cannot be guilty of running lane interference prior to reaching the beginning of the lane.

- The rule does not cover throws being made other than toward first base. In other words, a batter-runner cannot be guilty of running lane interference when the throw is going home, such as on a ground ball to the first baseman with a runner on third. Of course, the batter-runner could be out for another reason, such as intentionally interfering with the throw by where he has positioned himself.

- The running lane rule obviously becomes more possible the closer the batted ball is to home plate. This is because the batter-runner will not be allowing a natural path for the throw if the ball is near the plate and the batter-runner is in fair territory. This is not to say that the interference cannot occur on a throw say, from the third baseman. However, the rule is much less likely to come into play with a throw from that angle. The probability of the running lane interference increases with the decrease in the angle of where the throw is coming from. Say a third baseman is charging on a bunt; the more he moves toward the first base line in fielding the ball, the less the angle, and the increase in the importance of the batter-runner being in the running lane so that there is room to throw and receive the throw.

- When the rule is enforced the ball is dead, the batter-runner is out and all other runners must return to their time-of-pitch bases. The plate umpire points at the guilty batter-runner, yelling, “That’s interference! Time! He’s out!” and then returning other runners.

Perfect Practice Makes Perfect

If you have never paid much attention to this rule as an umpire, you will be surprised at how many “practice” plays you get when you become more aware of whether the batter-runner is using the running lane properly. You need to become tuned into knowing where the batter-runner is. Sam Holbrook did not nail his World Series play without a solid foundation of years of watching for possible violations.

Let’s work to make sure the running lane rule is not the most-missed in the high school game. Most importantly, let’s be umpires always seeking to make the game of baseball fair for all players. Part of that development is “keeping ‘em in the lane.”

https://www.mlb.com/video/search?q=Player%20%3D%20%5B%22Trea%20Turner%22%5D%20Order%20By%20Timestamp